For some reason, perhaps a hatred of humanity, when people talk about third-person objective (“fly on the wall”) narration, they always lead with Hemingway’s Hills Like White Elephants. This is a lousy story. It reads more like an exercise, not one of Hemingway’s better efforts at all, so we’ve started off on the wrong foot.

For some reason, perhaps a hatred of humanity, when people talk about third-person objective (“fly on the wall”) narration, they always lead with Hemingway’s Hills Like White Elephants. This is a lousy story. It reads more like an exercise, not one of Hemingway’s better efforts at all, so we’ve started off on the wrong foot.

Worse, it’s almost entirely dialog. You can tell a story that’s mostly dialog in any narrative mode, and it’ll come out the same. It’s not a showcase of third-person objective.

We’ll use a better example.

What Is Third-Person Objective Narration, Anyway?

If you take a third-person omniscient narrator who never bothers to report anyone’s thoughts or feelings at all, but just shows what’s happening in the room, as if they were an observer, that’s third-person objective.

In addition, the story usually follows a single character around, reporting only what happens in their general vicinity, and there are no flashbacks or nonlinear narration. Just one thing after another.

If you become fooled by the word “objective,” as so many have, you’ll think that there should also be a certain clinical, detached, robotic element to the storytelling as well. Don’t do that; it’ll suck the life right out of your story.

A Better Example

So let’s pick an example that’s suitable for our purpose: a well-known, highly successful story written by a highly successful author.

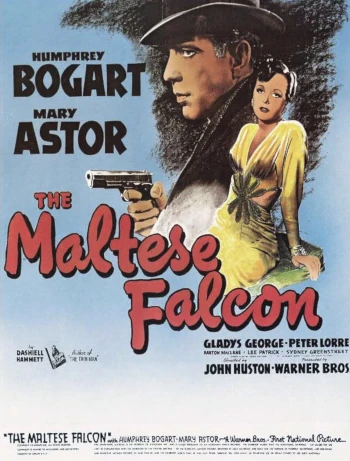

The author is Dashiell Hammett and the story is The Maltese Falcon. One of these days I may compare it to another famous detective story of his that doesn’t use third-person objective, The Thin Man (but not today).

The Maltese Falcon

The Maltese Falcon is a 1930 novel that is considered to be the first hardboiled detective novel. It’s on everyone’s short list of third-person objective stories, despite Hammett using narrative techniques that contradict much of what is said about third-person objective.

My verdict: Hammett was right. Conventional wisdom is wrong.

Hammett’s narrator tells the story without diving into anyone’s thoughts, so that part’s uncontroversial.

Also, the narrator never leaves Sam Spade’s presence. If Spade is unconscious or asleep, the narrative skips ahead until he wakes up. No flashbacks, no backstory except in dialog (which is mostly lies). No scenes told out of chronological order. All this is normal enough.

But objective? Let’s look at the opening sentence of a typical scene:

The eagerness with which Brigid O’Shaughnessy welcomed Spade suggested that she had been not entirely certain of his coming.

Note that this entire sentence is a complex value judgment about what Mrs. O’Shaughnessy’s behavior implies about her thoughts and feelings; thoughts and feelings the narrator never reveals directly.

There’s exactly zero “show, don’t tell” in this sentence, which is as it should be. For one thing, a new scene always requires some setup before we can start slinging subtext around. For another, the subtleties of body language and expression cannot be conveyed properly through direct physical description, so Hammett doesn’t try.

But drawing inferences about her mindset from her body language and behavior, reported only as “eagerness” and “not entirely certain,” are not objective observations. They’re guesses. They fall into the category of “mentalizing” or “cognitive empathy,” where you’re aware of what seems to be going on with the other person based on exterior clues. Nor are we aware of which clues we’re relying on, for much of this process is unconscious. That’s not “objective!”

In addition, to tell a story at all, you probably need sympathy as well (but not empathy; that’s optional), where you have a sense of the emotional interplay between the characters and events.

Without the emotional content, stories lose their meaning. We have to communicate this emotional content to the reader, one way or another. Being a blank wall of objectivity won’t cut it. We don’t have mind-reading in third-person objective, but we can report what any observer would notice and conclude. That’s the job of our narrator.

Let’s do a longer except. I’ve italicized the phrases that an objective narrator would be unable to say because they’re guesses, not fact:

He stood beside the fireplace and looked at her with eyes that studied, weighed, judged her without pretense that they were not studying, weighing, judging her. She flushed slightly under the frankness of his scrutiny, but she seemed more sure of herself than before, though a becoming shyness had not left her eyes. He stood there until it seemed plain that he meant to ignore her invitation to sit beside her, and then crossed to the settee.

“You aren’t,” he asked as he sat down, “exactly the sort of person you pretend to be, are you?”

“I’m not sure I know what you mean,” she said in her hushed voice, looking at him with puzzled eyes.

“Schoolgirl manner,” he explained, “stammering and blushing and all that.”

She blushed and replied hurriedly, not looking at him: “I told you this afternoon that I’ve been bad—worse than you could know.”

“That’s what I mean,” he said. “You told me that this afternoon in the same words, same tone. It’s a speech you’ve practiced.”

After a moment in which she seemed confused almost to the point of tears she laughed and said: “Very well, then, Mr. Spade, I’m not at all the sort of person I pretend to be. I’m eighty years old, incredibly wicked, and an iron-molder by trade. But if it’s a pose it’s one I’ve grown into, so you won’t expect me to drop it entirely, will you?”

“Oh, it’s all right,” he assured her. “Only it wouldn’t be all right if you were actually that innocent. We’d never get anywhere.”

“I won’t be innocent,” she promised with a hand on her heart.

“I saw Joel Cairo tonight,” he said in the manner of one making polite conversation.

Gaiety went out of her face. Her eyes, focused on his profile, became frightened, then cautious. He had stretched his legs out and was looking at his crossed feet. His face did not indicate that he was thinking about anything.

There was a long pause before she asked uneasily: “You—you know him?”

Seeming is Believing

Hammett sometimes uses words like “seemed” and sometimes he doesn’t. In general, using words like “seemed” highlight uncertainty and conjecture; omitting them is more telegraphic and makes statements sound more like facts, but without insisting they really are. The reader is unlikely to become confused by this.

As you’ve seen, the complex meanings ascribed to actions and expressions are essential to the scene; a mind-blind robot narrator wouldn’t be able to tell this story adequately.

Ignorant Narrators?

The narrator is pretending that all these statements are no more than guesses, though confident ones: since he never actually enters anyone’s mind, he’s implying that he can’t. Is this really true? Irrelevant.

The author knows for sure what the characters are thinking. The narrator is pretending not to. That’s how I think about it.

Speaking of ignorant narrators, I think the concept is bogus in third person. You’ll be told, “The narrator doesn’t know anything except what happens right there in the room.” This is unhelpfully weird because ignorance can be tricky. We always have to deal with the characters’ ignorance, the readers’ ignorance, and our own (possibly undetected) ignorance. Let’s not add yet another layer. Enough is enough.

“The narrator knows much and reveals little” gets you everywhere you need to go.

(Similarly, the “omniscient” in third-person omnisicent is irritatingly unhelpful. The “omnisicent” narrator has no artificial barriers preventing them from revealing whatever they like to the readers. That’s all. Or concealing whatever they like, for that matter. But they’re not godlike.)

No Viewpoint Character

There is no viewpoint character. Or, if you prefer, the disembodied narrator is the viewpoint character. There’s no trace of the third-person limited issue of, “The reader can’t know the viewpoint character has a KICK ME sign on their ass before the viewpoint character does” phenomenon. The narrator can show us Spade’s backside at any time.

Admittedly, I call Spade the viewpoint character myself, but all I mean is that we never get a glimpse into anything unless he’s present and conscious. He’s handled the same as any other character otherwise.

Recipe for Third-Person Objective Narration

-

- Take one standard omniscient narrator. Impose the following restrictions:

- Restrict the narration to the vicinity of the (so-called) viewpoint character (usually the room they’re in), and the times when they’re conscious.

- No flashbacks, no backstory, no nonlinear narration: we’re stick with the viewpoint character in the here and now, with chronological narration.

- No mind-reading. The inner thoughts and feelings of the characters are not revealed. The narrative eye is always outside the body of the viewpoint character and can move around the room at will, including looking at the viewpoint character from any angle. We always look at everyone from the outside.

- Now peel away and discard some conventional concepts:

- Discard the metaphors of “a fly on the wall,” and “camera view.” They’re nonsense. Flies and cameras understand nothing. Even if they did, they can’t tell stories in prose. We’ll introduce a better concept in a minute.

- Next, reject the concepts of “objective” and “detachment” with contempt. If you take them the least bit seriously, you’ll suck the life right out of your story. We’re playing a different game here.

- Characterize your narrator:

- Our narrator is presented as if they are present but unseen.

- That is, they are an alert, observant, well-informed, discriminating, interested, engaged disembodied observer. You can’t tell a story worthy of the name without some emotional involvement.

- The narrator has broad knowledge. They already know the name and purpose of everything around them, though they may not condescend to inform the reader.

- Our narrator has a fully functioning theory of mind and is capable of cognitive empathy and sympathy. They can tell the story so this is transmitted to the reader so the reader isn’t forced to perform guesswork over things that would have been obvious if they had been there.

- Remember these ground rules:

- Don’t be robotic or artificially clueless. A fly on the wall can’t tell the difference between a table and a chair. Humans can, and do. Pretending otherwise would be weird. Your narrator can and should use phrases like, “leaping up with barely concealed glee.” It doesn’t break the Robotic Narrator’s Oath.

- Human communication includes a great deal of conjecture, often reported as fact. This is perfectly legitimate, even essential, in our third-person objective story.

- Take one standard omniscient narrator. Impose the following restrictions:

Good luck!